Nuclear War: A Beginner's Guide to Survival

Because we're all beginners. Let's keep it that way.

We covered all the basics in part one, including a long list of sources. No long introductions this time, we’re going to jump right in.

[Obama] Administration officials argue that the cold war created an unrealistic sense of fatalism about a terrorist nuclear attack. “It’s more survivable than most people think,” said an official deeply involved in the planning, who spoke on the condition of anonymity. “The key is avoiding nuclear fallout.” — William J. Broad, The New York Times, December 15, 2010

Caveats

This guide will hopefully increase your odds of surviving a nuclear attack. However:

We don’t have a crystal ball. We can’t exactly test this stuff in the field, we’re butting up against state secrets, and we don’t know what a real nuclear exchange would look like. And there will undoubtedly be third-order effects we can’t predict.

There are no guarantees. You could do everything right and die anyway. The goal is to increase your odds of survival, no matter how small a percentage that is.

Even if you survive, you may not like the new world you’re in. Just one nuclear weapon used in combat would forever change the world in unforeseen ways.

But if the unthinkable does happen, we won’t know at what scale it’s happening, and we may not know for a long time after. In any case, the survival strategies are the same. Assume things will be okay until they’re not.

I’m not going to go into details on digging shelters because I haven’t done so myself, and I’m assuming you’re not going to do that either. For detailed instructions, check Cresson Kearny’s Nuclear War Survival Skills, which is freely available online. Kearny was one of the first hires at the Oak Ridge National Laboratory and was respected by the likes of Eugene Wigner, a scientist on the Manhattan Project, and Edward Teller, architect of the hydrogen bomb.

Is digging a bomb shelter a good idea? Maybe, since it could also do double duty as a storm shelter and root cellar. Plus, you could have it stockpiled with food, water, and supplies. But the key question is: would you be at home when the bomb hit? Maybe if you work from home and don’t leave often. I don’t encourage drastic action unless you can justify the trouble and expense.

Likely Targets

I’m sure one of the big questions on your mind is: “Am I likely to get hit?” There is much debate over the most likely targets in a nuclear war. None of us have a crystal ball, but we can make some educated guesses.

There is a map of likely targets floating around online that was supposedly published by FEMA in 1990. I have doubts, but it’s as good as any.

If you’re wondering why New Jersey would get bombed back into the Stone Age, it’s not to rid the world of Jersey Shore once and for all — there are many important military bases in the Garden State.

According to Kearny, the Soviets’ major targets at the time included:

Runways over 7,000 feet long, because that’s how much a B-52 bomber needs to take off. In the event of a “victory,” the remaining bombers in the air would be a lingering threat. (Believe it or not, the B-52 still makes up the bulk of our nuclear bombers.)

Major military targets, like bases, and especially anywhere nuclear weapons are housed.

Major cities. Washington, D.C. for certain due to its strategic importance.

We might assume that Putin has similar targets and that his top priority in an all-out nuclear war would be to destroy as many nuclear sites as possible to minimize retaliatory attacks. Destroying major American cities for fun would be a secondary objective.

“As long as Soviet leaders are rational they will continue to give first priority to knocking out our weapons and other military assets that can damage Russia and kill Russians. To explode enough nuclear weapons of any size to completely destroy American cities would be an irrational waste of warheads.” Cresson Kearny — Nuclear War Survival Skills

If you have an airport near you and you’re freaking out, you can measure the runway(s) with Google Earth’s measurement tool. Don’t call up the airport rambling about nukes and cause a national security alert.

You may ask me if you want to move. I don’t recommend it unless you feel a strong compulsion. I’m not rearranging my life because of Vladimir Putin.

Determining Your Blast Zone

Alex Wellerstein has created an excellent online tool called NUKEMAP that lets you simulate an atomic blast of any size at any location. Please use this amazing tool sparingly because the site is overloaded at the moment.

To get the most use out of NUKEMAP, identify the closest nuclear target to your home or work. For me, that’s probably Fort Campbell, home of the 101st Airborne.

Type in the name of your location, choose whether to simulate an airburst or surface burst and select the casualties and radioactive fallout checkboxes. After you enter a location, you can drag the pin around the map to pick the exact target. I aimed for the airfield and I figure the attackers would want to turn it into a smoking crater, so I chose a surface burst.

When you’re ready, click Detonate. Color-coded concentric circles appear around the detonation site. Anyone inside the red circle would likely die instantly. Anyone left in the green circle would likely die within a month from radiation, which is better than instantly. Or not, depending on your point of view. Beyond that, your chances of survival increase dramatically, especially if you’re well sheltered when the bomb goes off. The good news is you may have time to take shelter.

NUKEMAP isn’t perfect. For instance, it doesn’t take local topography into account. There’s also this automated and terrifying simulator.

Early Warning Signs

Nuclear missiles take time to travel and the United States has excellent detection and alert systems. We know this because Hawaii learned the hard way.

On the morning of January 13, 2018, people all over Hawaii received a dire message on their phones, from their TVs, and over their radios:

BALLISTIC MISSILE THREAT INBOUND TO HAWAII. SEEK IMMEDIATE SHELTER. THIS IS NOT A DRILL.

Spoilers: It was in fact a drill. One that went horribly wrong. I’ve never visited Hawaii, but I remember when it happened. It wasn’t just Hawaii freaking out for the next 38 minutes, the entire world’s jaws were agape.

It was a terrifying experience that led to a congressional investigation, but in a way, I’m glad it happened, for a few reasons:

It showed that the United States has excellent emergency alert systems.

It was a rare enough occurrence that people won’t dismiss future warnings as false alarms.

Pandemonium didn’t ensue. Hawaiians were terrified and took shelter, but all hell didn’t break loose. Maybe it was thanks to the Hawaiian spirit of aloha, but it gives me some hope.

“It wasn't hysteria — there were no shrieks or sobs — but people were scared.” — David Shortell, CNN

There are a few ways to make sure you get emergency alerts on your phone:

On an iPhone, go to Settings > Notifications, scroll to the bottom and make sure Emergency Alerts and Public Safety Alerts are on. If you use an Android phone, you’ll have to check the instructions for your model and version of Android.

Install the FEMA app and enable all alerts. There isn’t a specific one for global thermonuclear war, but I’m willing to bet they’ll make an exception.

Send the text message SHELTER and your ZIP code to 43362, which tells you if you have any nearby FEMA shelters and opts you into FEMA text messages.

An old-school warning method recommended by Kearny is to listen to your radio. If it suddenly goes silent and you can’t pick up any other stations, that’s an indication of a possible EMP and you should seek shelter immediately. Hopefully, there will be an alert over the radio before that point.

Nuclear Launch Detected

Let’s say your phone warns you of an incoming missile. What now?

The good news is missiles take time to travel. You have anywhere from 10 to 20 minutes to take shelter. Assume 10. Quickly set a timer and grab your go-bag if you have time.

You need shelter to protect you from the initial explosive blast, the burst of heat and radiation, and the windstorm. Three points to remember:

Get inside

Stay inside

Stay tuned

Before this point, you can identify potential shelters in your usual haunts (home, office, gym, etc.), which may also be helpful for tornadoes. A lot of the advice is the same. Here’s what to look for:

You ideally want to be surrounded by thick earth, concrete, or both. Per Nuclear War Survival Skills, the gamma radiation halving thickness of concrete is only 2.4 inches. If the shelter is surrounded by other dense buildings, even better1.

Any building is better than no building.

Underground is better than above ground.

If you’re above ground, you want to be near the center of the building near a wall. Below ground, go to a corner2.

Stay away from windows. You could survive the blast only to be killed by exploding glass3.

You want to be laying flat face down on the ground when the bomb hits. Stay there until you feel two shockwaves. It may also help to have your mouth open, as it offers a path for pressure to leave your head without bursting anything.

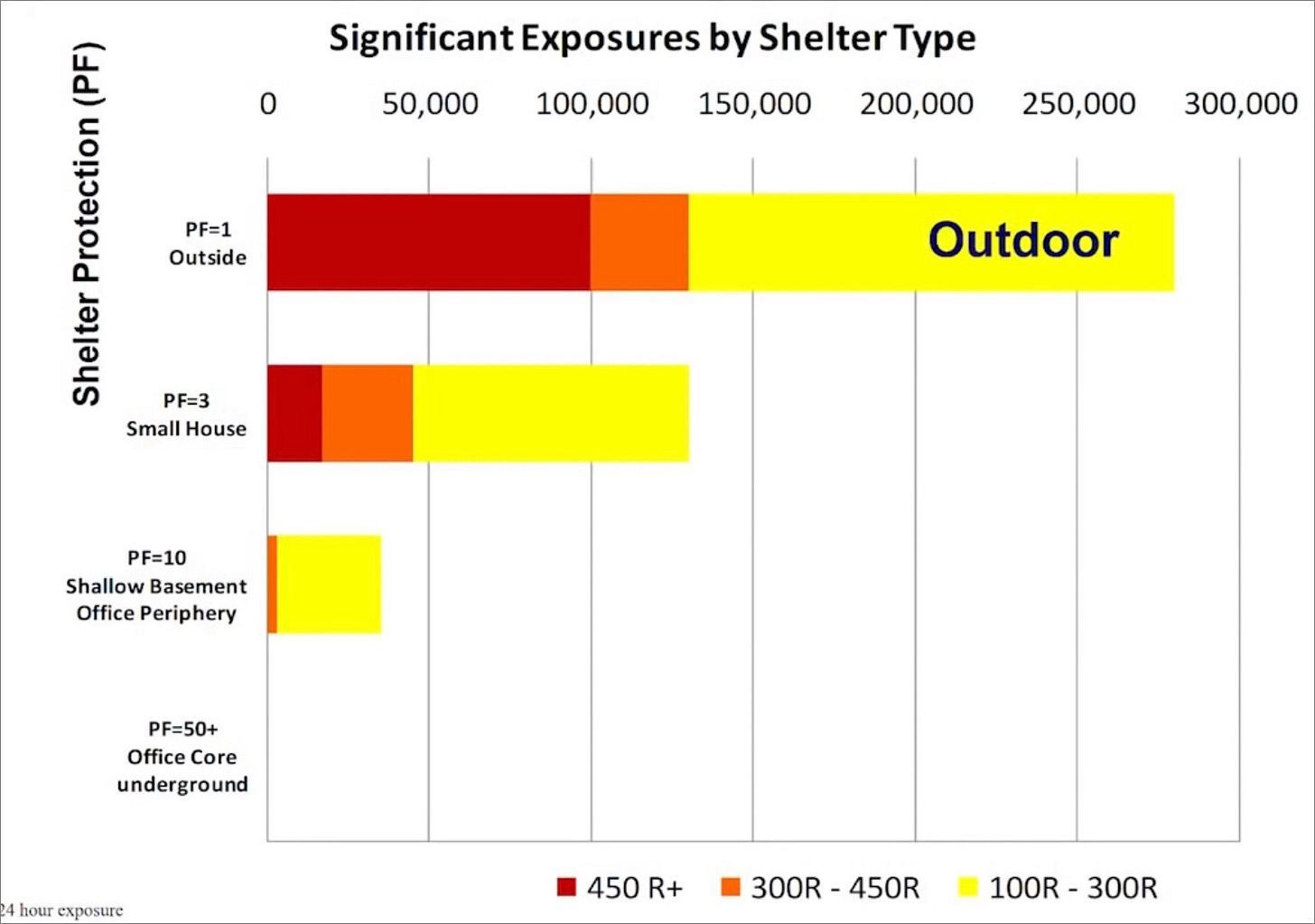

Believe it or not, these strategies could save many lives. This jaw-dropping chart from FEMA’s Brooke Buddemeier shows the difference in how many people would suffer severe radiation exposure after 24 hours depending on how well they were sheltered:

Watch the full talk. It’s amazing and surprisingly reassuring. I’m glad we have even-keeled folks like Buddemeir in high places.

What if you’re on the road or can’t get inside? Here’s how to increase your odds:

If you are stuck on the freeway, you need to stop the car and pull over. If you’re temporarily blinded while going 60 mph you will be a hazard to yourself and others. Close the windows and duck down in the vehicle if you have no better shelter.

If you are trapped outside and cannot find any shelter, lay flat at the foot of a hill and cover yourself with a blanket or whatever you can find to shield yourself from the heat. If there’s no hill, lay behind a log, rock, or in a depression4. Whatever you’ve got. If an evil subterranean clown offers you a red balloon, consider taking him up on it.

Again, lay flat face down on the ground and keep your mouth open. Tuck your hands and arms under your body. Stay there until two shock waves have passed.

It is absolutely imperative to shield your eyes from the flash. The blindness may only be temporary, but those minutes or hours could be the difference between life and death.

If you do get flashed, shut your eyes and dive for the ground. It’s your best chance of survival.

We Need to Talk about Potassium Iodide

A shocking number of you bought potassium iodide pills based on my recommendation. I tried to be clear about the dangers and honest about the use cases, though I mistakenly said it prevents radiation poisoning when in fact it prevents thyroid cancer, which is also something you don’t want. In any case, I want to make sure you know the facts and I’ve been flooded with questions.

Full due diligence: this guy, Phillip Broughton, is a health physicist at Berkely and says to not take it at all unless told by a doctor or public health department. However, in a nuclear crisis, that may not be an option. (Even getting a COVID test from my health department was nigh impossible in 2021.)

So understand:

Potassium iodide is safe when used as directed, but an overdose will kill you. I understand that it’s an unpleasant death. Do not take it for fun. Do not take it for an extended period. Lock it up like you would a gun and/or ammunition.

Potassium iodide prevents thyroid cancer by flooding your thyroid with non-radioactive iodine. It won’t protect you from the blast, radiation sickness, or fallout.

Take only the products approved by the FDA for this purpose. iOSAT and ThyroSafe are the two usually available. I cannot vouch for any other product. If you take an ineffective product you will not know it until you get thyroid cancer.

I know supplies are largely sold out now. I’ve received many questions about buying pure potassium iodide powder from a chemical supplier and dosing it out yourself. I do not endorse that unless you are a pharmacist or chemist and know what you’re doing.

Be wary of online scalpers, who are selling potassium iodide for 10x the usual price. There may also be counterfeit products out there now to take advantage of the high demand.

Iodine drops are not sufficient. Remember: Potassium iodDIDE not iodDINE.

The pills supposedly still work after the expiration date but may work more slowly. Add the expiration dates to your calendar and keep your supplies fresh.

People have asked me when to take it. Biologist Ari Allyn-Feuer says to take it before the bombs hit because you want your thyroid saturated before you’re exposed to radiation. Frankly, if nuclear bombs are dropping, I’m fine with you taking any pill that makes you feel better.

Surviving the Fallout

Sheltering is one of the most, if not the most, important protective action that affected populations can take in the first few hours after a nuclear explosion. Sheltering can save lives by protecting people from radioactive fallout and the inhalation of dust and smoke. — FEMA

You’re alive? Congratulations! If you’re still outdoors you have about 15 minutes before fallout starts to rain on your head, which will look like ash or snow. Get inside ASAP if you can. If you’re inside, stay there. If you’re inside a house, turn off your HVAC or anything that could suck fallout indoors.

How long? That is a matter of debate and also depends on the size of a bomb, whether it was an airburst or surface burst, etc. An airburst produces much less fallout because it’s not throwing chunks of radioactive ground into the air.

Brooke Buddemeier says a few hours to about three days, assuming a smaller bomb. Cresson Kearny said two weeks or maybe longer. How long you can realistically shelter is going to depend on your supplies, if any, and shelter conditions, but if you can hold out at least 24 hours before taking a peek outside, do so. If there are rescue workers, they may find you in that time. The longer you can sit tight, the better. This is where a fully stocked home shelter would be nice.

You also want to be tuned in to information sources if you can. Authorities may offer guidance on whether it’s safe to move. Don’t expect cellular networks or the power grid to work due to the EMP. A radio is best here, though picking up anything may be impossible if you’re underground. It may be safer to move to a higher floor and quickly tune in than running outside — if that’s an option.

When the time comes to leave the shelter, protecting yourself from fallout is key:

Cover as much skin as possible to keep fallout off of it. Wear long sleeves, a hat, gloves, a poncho, a trash bag, whatever you have. It doesn’t have to be a special material.

If you don’t have gloves, keep your hands in your pockets.

Try to prevent breathing in fallout. A respirator would be good here. Failing that, wrap a wet cloth over your mouth5.

Avoid eating food or drinking water contaminated by fallout. Opt for bottled water and packaged food.

Keep out of the rain, which could dump huge amounts of fallout on you.

Avoid trees. Fallout on the branches may drift down on you.

Stay away from the blast site. It may be radioactive.

If fallout comes in contact with your skin, rinse it off immediately with water. Soap too, if available.

When you reach your destination, you need to decontaminate. Quickly shake off as much fallout from your clothes as possible without touching it with bare skin. When you get indoors, strip, put your clothes in a bag and immediately wash with water and soap. Do not use conditioner, which could cause the fallout to cling to your hair.

It’s good to have disposable ponchos and trash bags in your kit to keep fallout off your clothes and to have somewhere to dispose of them.

Preps and Gear for Nuclear War

For a general-purpose go-bag, I refer you to The Prepared for now. An expert panel spent weeks debating the gear recommendations and I hesitate to monkey with them. However, much of the kit is based on outdoor survival, so I’ve made a spreadsheet of gear more specific to nuclear prep. I’ll highlight a few items here.

You’ll want the ponchos and trash bags mentioned above. For trash bags, get 3 mil contractor bags. They’re big and thick, so you can use them to cover your clothes, make a bed, and bag up trash, excrement, etc. Super useful in many situations.

Radiation dosimeters are invaluable for measuring your radiation dosage, but they’re not available to the general public, so I included the RADTriage Model50 with some hesitancy. It’s a wallet-sized dosimeter approved by the Department of Homeland Security (PDF link), but there have been many complaints of quality problems and it only lasts a couple of years. Cresson Kearny includes simple instructions for building a fallout meter in Nuclear War Survival Skills. If you’re interested, buy the hard copy because it includes templates and you want to make sure they’re the correct size.

Radio is essential for listening to emergency broadcasts. Any AM/FM radio will do, but I love the C. Crane Skywave SSB, which lets you also listen to weather, shortwave, airband, and ham radio. I recommend it if you have the extra dough, but it’s not a priority. Don’t forget batteries!

You’ll want some sort of first aid kit. At the very least, you want bandages, a tourniquet, anti-diarrhea meds, anti-nausea meds, and whatever medications you require. Maybe nicotine patches if you need them (nuclear war is not an easy time to quit!). My friend Tom Rader is an actual medic who served with Marine Recon. He now sells high-quality individual first-aid kits for around $200. I’ve assembled a near-identical kit and spent at least that much. I’ll be reviewing his kit in the future.

I also threw in pepper gel spray for self-defense. Things will be stressful and someone could get violent. A gun may be a terrible idea here for several reasons. Pepper spray lets you end an encounter without lasting physical harm. Gel spray because it’s the least likely to hit innocent bystanders in an enclosed space.

Check the spreadsheet for the full kit and explanations.

Put your kit in a discreet bag, like a Jansport backpack. Keep it where it’s readily accessible, like the trunk of your car. If you frequently take public transport, maybe keep just a few items in a backpack. Water is the most important item.

Note that most of the recommended items here are useful for many scenarios, not just a nuclear attack. We don’t want you wasting your money on uni-taskers.

Life After the Day After: Is Nuclear Winter Real?

Nuclear winter is a hypothesized aftereffect of a nuclear war, popularized by the late astrobiologist Carl Sagan. The concept, based on scientific models, is that a nuclear war would send so much soot into the atmosphere that it would block the sun for years, leading to global cooling and mass famine. Robinson Meyer recently published a piece in The Atlantic talking about the potential environmental devastation.

Most of us accept nuclear winter as a foregone conclusion, but it’s up for debate. MIT meteorologist Kerry Emanual wrote “nuclear winter” is “notorious for its lack of scientific integrity.” Scientist Russell Seitz argued in Nature that “Nuclear winter was and is debatable.” William R. Cotton, a respected climate scientist and early proponent of the nuclear winter hypothesis, has since reversed his position, writing, “It is clear that nuclear winter was largely politically motivated from the beginning, and it is an example of science being subverted to political ends.”

Interestingly, when Saddam Hussein set fire to Kuwaiti oil fields in 1991, Sagan predicted that it would cause a nuclear winter-like event. That didn’t happen. That doesn’t mean the nuclear winter hypothesis is wrong, or that Sagan was a bad scientist, just that models don’t necessarily line up with reality.

Is nuclear winter a real possibility or merely a myth? Let’s hope we never find out.